How a mattress is made − inside the mattress factories at IKEA, Hästens, and 3Z

I've traveled from the heart of Arizona to the slopes of Scandinavia to see how foam is poured and springs are coiled to make the world's best mattresses

As H&G's resident sleep editor, I'm often asked how a mattress is made. The answer depends on the mattress type, as well as where you are in the world, and how much money you're prepared to spend.

Since I took over our sleep category, I've visited three mattress factories: one in the US, and two in Sweden. I've toured a vertical manufacturing plant that's packed with heavy machinery as well as a smaller, family-run factory where most of the work is done by hand. I've worked with memory foam and horsehair to help make mattresses that cost hundreds, no, thousands, or even tens of thousands of dollars.

I've seen first-hand how the best mattresses are made – now, I want to share my insider insights with you. I'll take you onto the factory floor at 3Z Brands in Glendale, Arizona, home to the Brooklyn Bedding, Bear, Helix, Birch, Leesa, and Nolah mattress brands. Then, I'll show you behind the scenes at Hästens in Köping, Sweden, where the world's most expensive mattress is made. I'll even let you into the IKEA Test Lab in Älmhult, Sweden, where mattresses are stress-tested for pressure relief, thermoregulation, and durability.

How a mattress is made – our sleep editor investigates

Before I can explain how a mattress is made, we need to refine the question: exactly what type of mattress are we talking about? Here's a brief overview of the most common mattress types and their material make-up, plus some pros and cons.

What's in a mattress?

Most modern mattresses are formed of three layers: a support layer to bear your weight; a comfort layer to relieve pressure; and a cover layer to encase the mattress. Which materials make up each layer depends on the type of mattress you're looking at. Here's a quick intro to the most common mattress materials.

- Steel coils: often found in support layers, steel coils are springy and responsive to bear your weight and keep your spine straight. You'll find steel coils inside innerspring and hybrid mattresses. With each compression and decompression, coils circulate air through the bed, which makes for cooler sleep. In most modern designs, steel coils are pocketed, or individually wrapped in fabric, to minimize motion transfer: good news for light sleepers and anyone who shares a bed.

- Memory foam: made from polyurethane. How foam feels depends on its density. High-density foam feels firm: it's the sort of foam you find in support layers. Lower-density foam feels softer and moves slower, so it's better suited for comfort layers. Memory foam offers excellent pressure relief and motion isolation, so it's great for anyone who suffers from chronic pain. Still, like any synthetic material, memory foam is less breathable than natural fibers, so it's less suitable for hot sleepers.

When I assigned hot sleeper Jamie Davis Smith to test a memory foam mattress, she was skeptical. That was until she tried Nolah's patented AirFoam, which is perforated with strategic air pockets to boost breathability.

You can find more detail in our Nolah Original Mattress review.

A hybrid mattress marries the airflow and support of an innerspring with the pressure relief and motion isolation of a memory foam mattress. You get the best of both worlds. Our Head of Interiors, Hebe Hatton, started sleeping on the Leesa Legend Chill over summer, and she's loving it so far.

Our review of the Leesa Legend Chill Hybrid Mattress is coming soon.

My sister keeps this mattress in her guest room, so I sleep on it every time I stay over. If you sleep on your back or stomach, or you appreciate a firmer surface, then you'll find a lot to like about this old-fashioned innerspring. If you're a side sleeper, and you know you need a bit of plush comfort, try pairing it with the best mattress topper.

- Latex: there are two methods of making latex. In the Dunlop method, latex is whipped into foam, poured into a mold, and baked in a vulcanization oven at 212°F. You'll find Dunlop latex in support layers: it's firm and inflexible. In the Talalay method, latex is whipped into foam, poured into a mold, then vacuum sealed, frozen, and injected with carbon dioxide. This produces softer, springier latex, with plenty of air bubbles to boost breathability. Each production process requires a lot of energy, which raises costs, and makes latex mattresses more expensive.

- Wool: you tend to find wool in comfort layers. Wool is naturally thermoregulating and moisture-wicking. According to the Woolroom Clean Sleep Report, wool can hold up to a third of its weight in water before it evaporates, so it's a great option to combat night sweats.

- Horsehair: horse hairs are hollow, which makes for quick thermoregulation and enhanced breathability. If you look at a horse hair under a microscope, you'll see that it looks like a small coil, all curled up. That makes a mattress feel more buoyant, which aids pressure relief. It's relatively labor intensive to source, clean, and separate horsehair, which makes it a more expensive mattress material.

I sampled 43 mattresses in the 3Z showroom. Springy and responsive, cool and comfortable, the Bear Natural was my favorite. I called it home for long-term testing and I've been sleeping on it since the middle of June.

You can find more detail in our Bear Natural Mattress review.

'As a health-conscious sleeper, investing in natural materials gives me real peace of mind and helped me learn how to sleep better,' says News Editor Sophie Edwards. That's the wonder of organic wool, along with its natural thermoregulation.

You can find more detail in our Woolroom Hebridean 3000 Mattress review.

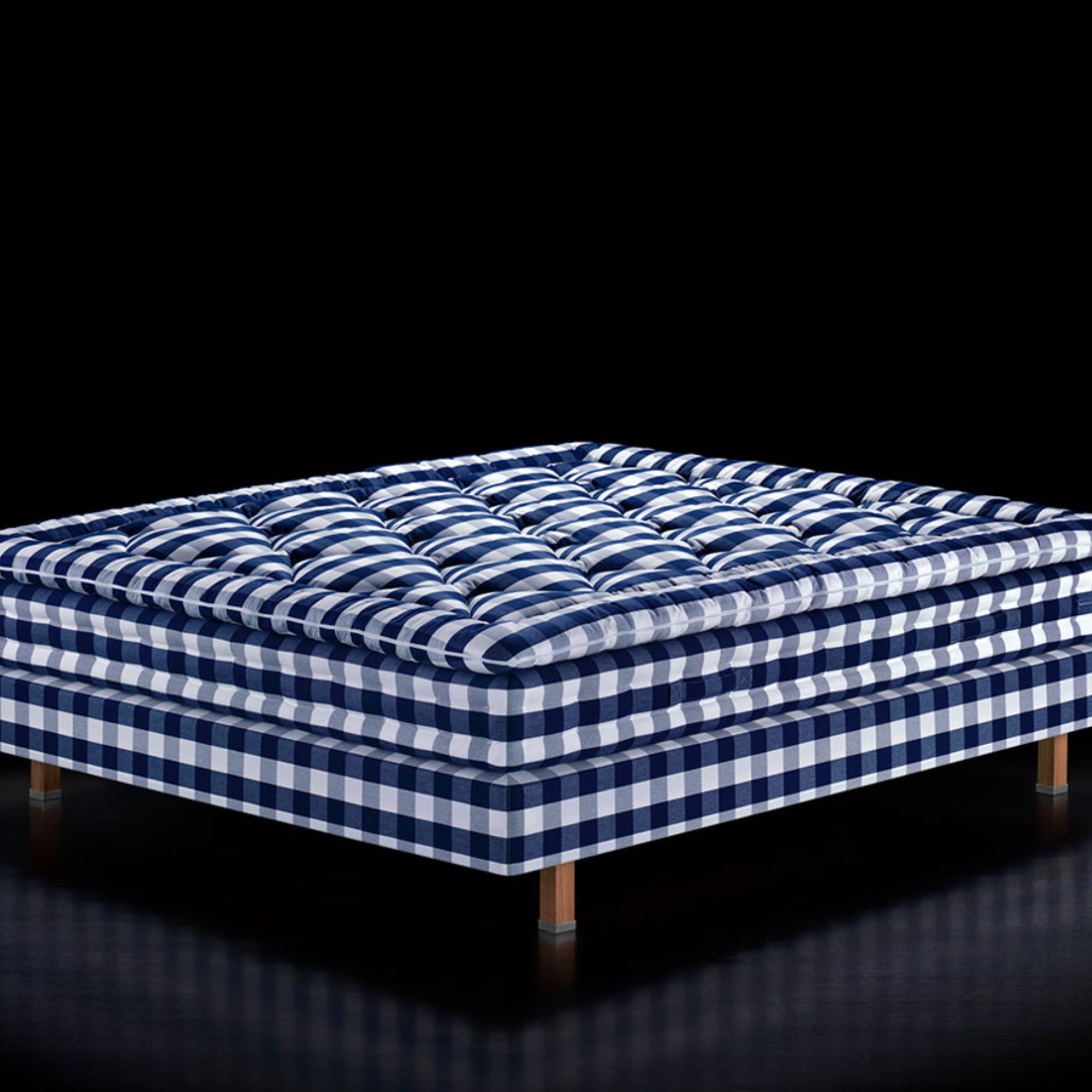

No official review for the Maranga Mattress: I only slept on it for a night in the Stallmästaregården Hotel in Stockholm, Sweden, but I'm still dreaming about it. The Hästens Maranga Mattress is softer than I'm used to, but super supportive.

You can find more detail about the Maranga Mattress in my account of the Hästens factory tour.

How a mattress is made − on the factory floor

The 3Z factory is a vertical manufacturing plant. 'That means we make our own materials, pour our own foam, and box our own beds,' explains John Merwin, CEO of Brooklyn Bedding and my tour guide for the day. It should come as no surprise, then, that the 3Z Brands mattress factory is big: 650,000 square feet, to be exact. 3Z uses this space to produce 2,200 mattresses a day across the six brands in their portfolio, though John estimates they could make 4,000 mattresses a day if they worked at full capacity.

During my factory tour, we zig-zagged from station to station depending on where the action was, so I'll try my best to put the mattress making process into chronological order. First, a team of seamstresses make the mattress cover using industrial-sized sewing machines. Meanwhile, the foam is formulated to meet a specific sleep need: springy and responsive for light sleepers, slower-moving for pressure relief, and so on. The foam is poured into a large mold, where it expands and solidifies into what John fondly refers to as a 'loaf'. Once you reach 100 feet of foam, the 'loaf' is cut, and the first 'slice' is sent to cure in the desert heat. Only once the foam is dry can the slices be stacked for storage: otherwise, the foam would start to compress.

Design expertise in your inbox – from inspiring decorating ideas and beautiful celebrity homes to practical gardening advice and shopping round-ups.

During this time, the steel is coiled into springs. Each coil is wrapped in fabric to create a pocket, so that when you apply pressure to one coil, the surrounding springs are not affected. This makes for enhanced motion isolation. All that's left to do is put the parts together and wrap them for delivery.

Things look very different over in Köping, Sweden. Where it took two hours and more than 2,000 steps to walk the mile around the 3Z factory floor, the Hästens factory is built on a smaller scale. There are 80 or so artisans working on the factory floor, separating horsehair, sewing stitches, and sanding wood.

Most notably, no noise, and very little heavy machinery. The bulk of the work that goes into making a Hästens mattress is done manually. I got to participate in the mattress making process, teasing the horsehair and completing a side stitch, which took me about five minutes, compared to my tour guide's ten seconds. It made me realize just how much skill goes into making a mattress – even more so when you're working by hand.

If you're making a box mattress, then the final stage of the process is the most important: the packaging. 3Z makes some of the world's best box mattresses. I've seen thick layers of foam get glued together, compressed and wrapped in plastic, and vacuum-sealed to keep everything airtight and delay decompression. The mattress is rolled into a cylinder and funneled into a cardboard box, which is delivered straight to your door.

In the modern age of online mattress shopping, most mattresses are box mattresses, but the team at Hästens likes to uphold tradition. A Hästens mattress is also wrapped in plastic for protection against dust and dirt. Rather than making the mattress fit the box, the team at Hästens make the box to fit the mattress. A cardboard case is constructed around each section of the mattress, which arrives in two parts, driven to your door. Now, the real work begins – lugging thick layers of steel coils and horsehair upstairs and into the bedroom.

How a mattress is made − in the lab

Before a mattress model can make its way onto the factory floor, designers must produce a prototype and subject it to rigorous testing. I visited the Comfort Suite of the IKEA Test Lab to see that process play out. That's me in the photo: the one laying down on the IKEA mattress, which is connected to a computer to take my vitals.

'When we test a mattress for mass production, we're interested in three things,' says Susanna Wadensjö (Test Development Engineer). 'Pressure relief; indentation; and microclimate.' The ideal mattress strikes a careful balance between comfort and support: soft enough to cushion your joints, but solid enough to keep your spine straight, and strong enough not to sag.

From the moment I lay down on the mattress, Susanna started taking measurements, producing a thermal map to visualize the data. I could see a dark smudge near the foot of the bed (the weight of my big black boots) and slightly lighter smudges around my hips and shoulders. Susanna explained that this is where I carry the most weight, so this is where the mattress needs to be most supportive. This is when designers might tweak the distribution of materials through the mattress to reach the ideal ratio of comfort versus support layer.

To measure thermoregulation, Susanna introduced Ove − a space heater come water tank, which rhythmically rocks back and forth across the mattress, radiating heat and moisture. Susanna generated another thermal map in shades of blue and red to show how effectively the mattress works to dissipate heat and wick moisture. The ideal mattress should be all blue, or close to it, without any hidden heat pockets to aggravate your night sweats.

Before their mattress can make it to market, designers must prove that it is comfortable, supportive, breathable, and – crucially − durable. That's where Fredrik Lennartsson (Test Development Engineer) comes in. Fredrik operates the stress-testing machine: a motorized cylinder which lowers onto the mattress, then rolls from side to side, exerting pressure. Over in the 3Z factory, they call this sort of machine 'the Rollinator.'

The IKEA Rollinator applies 1400N of force to a mattress. According to Fredrik, that equates to the force of the average adult man rolling across his mattress. The Rollinator runs for five hours, with a brief pause every 100 cycles, until it reaches 30,000 rolls. Fredrik says this is equivalent to 10 years of nightly use − hence IKEA's 10-year mattress warranty.

'At this stage of production, I want to push a mattress to its limit – and beyond,' says Fredrik. 'I want to know: when does it break? How does it break? What can we learn from that?'

Once a mattress makes it out of the lab, onto the factory floor, and out into the market, it's ready to call in for testing. Much like the team in the IKEA Test Lab, I'm interested in pressure relief, weight distribution, and thermoregulation, as well as motion isolation, edge support, and the all-important price. To learn more about how we test mattresses at H&G, consult our expert guide.

Emilia is our resident sleep writer. She spends her days tracking down the lowest prices on the best mattresses and bedding and spends her nights testing them out from the comfort of her own home. Emilia leads a team of testers across America to find the best mattress for every sleep style, body type, and budget.

Emilia's quest to learn how to sleep better takes her all around the world, from the 3Z mattress factory in Glendale, Arizona to the Hästens headquarters in Köping, Sweden. She's interviewed luxury bedding designers at Shleep and Pure Parima, as well as the Design Manager at IKEA. Before she joined Homes & Gardens, Emilia studied English at the University of Oxford.